Dear Reader, in this age of AI created content, please support with your goodwill someone who works harder to provide the human-made. Sign up at the top of the lefthand column or bottom of this page. You will receive my hand illustrated monthly newsletter RESTORE NATURE and access to the biodiversity garden design course as I write...and nothing else, I respect your time. I am also removing the advertizing as best I can as its become intrusive inappropriate and pays me nothing.

Aforestation based on an observed forest ecosystem

Hostile aforestation. Wild almond, one of the few indigenous trees planted by the early Dutch at the Cape. They were planted to fence out the indigenous inhabitants of the land. Mostly the Dutch preferred to fell indigenous forests. Once covering many south east slopes of Table Mountain, they are now only ink in the diary of the bitter almond planter.

Hostile aforestation. Wild almond, one of the few indigenous trees planted by the early Dutch at the Cape. They were planted to fence out the indigenous inhabitants of the land. Mostly the Dutch preferred to fell indigenous forests. Once covering many south east slopes of Table Mountain, they are now only ink in the diary of the bitter almond planter.The human who creates forests rather than destroying them

When forests have been destroyed there is often resignation, and the belief they cannot be recovered. However, recovery has been shown to be possible. Not only that, aforestation need not apply on a grand scale. Micro forests on a hundred square metres, manmade forest in an industrial wasteland, these ideas are not some fevered wish, but the life long output of the world’s great experts in rapid forest regeneration: Akira Miyawaki and lately Shubhendu Sharma.

Many many years ago, before I was born, and I’m close to sixty now, a young Japanese botanist and ecologist observing different forest patterns in Japan began to evolve a method for restoring forests from industrial wasteland. His inheritance has grown and this knowledge has become widespread in the east, but in the west, the age old tenets of forestry which Miyawaki’s methods overturn, have remained dominant. The knowledge systems of Bill Mollison and Jeff Lawton are one of the few ways in which ecosystemic thinking has spread to the west.

A self sustaining forest has plenty of dead wood feeding fungi

A self sustaining forest has plenty of dead wood feeding fungiRoute to successful aforestation

The way aforestation is usually done in the west is pretty sad. Just planting trees is not enough. There is so much desire and passion but you have to understand relationships of size, distance, number and chemistry in the tree plantings. It is the ecosystemic method that makes the difference between success and failure in the regeneration of forests.

waist high indigenous ornamentals in cleared space, medium high unplanted forest (mid ground) and towering pine plantations (rear) in the botanic garden represent various stages in value laden thinking about our forests

waist high indigenous ornamentals in cleared space, medium high unplanted forest (mid ground) and towering pine plantations (rear) in the botanic garden represent various stages in value laden thinking about our forestsmicro forests, aforestation with minimal time to maturity and maximum diversity and sustainability

It is not alone the tiny size needed (100 square meters) or the place (Industrial wasteland) which makes ecosystemic aforestation so spectacular, but the time (ten to thirty years) to recovery. They are able to regenerate to trees of substantial height in ten years, and forests of rich, dense and protective pioneer forest in thirty years, whereas a naturally regenerating forest can take 200 years in a temperate climate like Japan’s and up to 500 years in the tropics.

Not only this, but they are self sustaining after two years of supervision, as the forest microclimate takes over to insure adequate moisture and nutrition for growing trees is supplied by the forest itself.

And one more plus, as if this wasn’t enough, the end result can have greater species diversity than natural forest.

light up ahead

light up aheadThe ethos of ecosystemic aforestation

The development of the Miyawaki method in Japan owes much to Miyawaki’s extremely observant eye. He noticed that the groves of trees around holy places and cemetries were different in composition to most forests in Japan. They contained higher percentages of deciduous trees in the oak, chestnut and laurels families. These groves of trees were protected because interfering with them was considered very unlucky. He showed that these were remnants of the primary forest which now comprised merely 0.06% of Japan’s forests.

The conifers which even botanists took to be indigenous were in fact alien trees that had been introduced for timber over the centuries. The composition of most Japanese forests reflected forestry planting patterns which he believed were not as resilient, suited to Japan or adaptive to climate change.

Miyawaki used the tradition of sacred groves as a basis for restoring native forest. He became less interested in the productivity of the forest for forestry and more interested in allelopathy, that is the beneficial or detrimental effects different plant species have on each other or other organisms like herbivores via allelochemicals, or secondary metabolites, and he also became interested in the complementarity of species, or the compensatory dynamics in ecosystems between plants with different ecosystem functions.

His method for restoring forests aims for a composition of plants closer to the original indigenous forest, which has greater stability, internally as well as suitability to climate.

Today's seed catch, the fruit of a long lost continent: Gondwana

Today's seed catch, the fruit of a long lost continent: GondwanaMiyawaki: healing the earth

scientifically

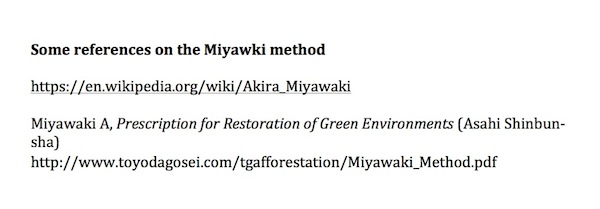

Akira Miyawaki was born in 1928 and became a botanist via the usual academic route. He specialized in the study of forest ecology and seeds. He was invited to Germany by Reinhold Tuexen and worked with him for 2 years (1956-8). They honed plant survey techniques for determining the vegetation types that would occur naturally in an area without human interference, or the concept of potential natural vegetation (PNV). He went on to develop a methodology for planting successful forests. This ecological reforestation called the Miyawaki method has yet to really take hold in the western hemisphere, although it has been around for so long.

After a long struggle for acceptance, Nippon steel gave him the opportunity to plant forests at eight of their steel mills. He went on to plant 1300 sites in Japan on deforested and degraded land, which no longer had humus, on urban, port and industrial lots, roadworks, dynamited cliffs, wastelands, power plants and artificial islands. These shelter belts and woodlots also protected water sources and prevented disaster by acting as windbreaks.

During his working life Miyawaki inventoried over 10,000 sites such as sacred groves in Japan as well as mountains, river banks, village perimeters, and urban areas. His maps of PNV still serve as a model to restore degraded habitats in Japan.

He also showed that after the destruction of rain forests, rapid restoration was possible through the choice of pioneers and secondary indigenous plants, closely planted and inoculated with fungi. He would study the local plant ecology and use species with the right niches in the tree community as key species, as complementaries, and usually planted up forty to sixty support species.

He formed a seed bank of ten million seeds classified by their geographical origin and soil which are mostly from the forest remnants in sacred groves descending from prehistoric forests.

He has done vegetation surveys in Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia and has planted 40 million native trees around the world to contribute to forest regeneration. His forests in the tropics grow at an average of one meter per year and some are now twenty meters high.

The method Miyawaki created has also been tested for the first time in a brittle Mediterranean climate in Sardinia in 2000. Where traditional reforestation methods fail, this method succeeds. After 11 years biodiversity was very high and the forest is self supporting.

A recovering forest, so dense it is impossible to walk in it

A recovering forest, so dense it is impossible to walk in itThe steps in Miyawaki's method

of aforestation

The success of the Miyawaki aforestation method depends on the following:

A thorough survey of the site and research on the potential natural vegetation at that locality

Identification and collection of native seeds, nearby, local and in similar climates.

Germination of the seeds, which can be quite tricky and require special techniques for some species.

Rehabilitation of any degraded soil with organic matter. Consider the root formations of these plants and supply their needs, such as using planting mounds for tap root species that require a well drained soil surface.

Planting for biodiversity, but modeling on natural forest.

Planting very dense, 30 – 50 plants per meter squared in temperate areas and and up to 1000 plants per square meter in tropical rain forest. Density encourages competition and phytosociological relationships to develop. Plant young seedlings with a well developed root system including symbiotic bacteria. For example, two year old, 30 cm oaks.

Distribution of planting and plantations randomly in space not in rows or staggered rows. (see my 3 methods for creating natural looking planting patterns)

On the forest edge I found this lovely false pea tree, a nitrifier. Many other allelopathic relationships in our forests are not understood, we are at the beginning of a steep learning curve.

On the forest edge I found this lovely false pea tree, a nitrifier. Many other allelopathic relationships in our forests are not understood, we are at the beginning of a steep learning curve.Speed aforestation hasn't taken root in the western hemisphere

This will quickly produce a multi-layered forest and a soil which quickly approaches that of normal primary forest. IN twenty to thirty years there should be a restored forest with genetics, humus, and percentage of old wood that strongly resembles a native forest.

This method has been extensively tested and proven successful in dry tropical forests in Thailand, alluvial tropical forests in the Amazon and in beechwood forest in Chile, a forest of Quercus mongolica along the great wall of China, and huge tree planting events in China, Vietnam and other areas in the East continue to this day via the Japan based company Aeon.

Despite more than a thousand successful projects, the western hemisphere forestry bodies have rarely attempted to apply or test the Miyawaki method. One of the only criticism is that it produces ‘monotonous’ looking forest with trees of the same age, at 20 years. Miyawaki always spoke against planting in straight lines an equal distance apart. Trees which have been damaged add to the richness of the system and resprout to create more understory. Another criticism is the high cost. Against this is the success of the method when normal thin monocultural forestry plantings fail, and the fact that it needs so little maintenance.

Any old niche plant from any old place is not good enough

Studying and reproducing local ecosystems is important. The introduction of exotic nitrogen fixing bacteria on N fixing exotics like lupins has created a problem with invasion and extinction on the microscopic level, so ecosystemic gardeners beware.

------

home page for plenty of tips on natural gardening

------

------

beautiful trees and beautiful people,

Restore Nature Newsletter

I've been writing for four years now and I would love to hear from you

Please let me know if you have any questions, comments or stories to share on gardening, permaculture, regenerative agriculture, food forests, natural gardening, do nothing gardening, observations about pests and diseases, foraging, dealing with and using weeds constructively, composting and going offgrid.

What Other Visitors Have Said

Click below to see contributions from other visitors to this page...

Anyone done this in Cape Town?

I live in Plumstead, which is quite a tough place to garden.

Anyone that you know of tried to plant a Miyawaki forest in Cape Town? I'm tempted to …

You’re a home gardener ! Share your experiences and questions !

We all know about home gardening. Tell us about your successes, challenges and ask about issues that bother you. You may have the luxury of a back garden, but there are other ways we learn. Few people age without growing something or buying vegetables during their lives ! It is absolutely guaranteed that you have learned things which can help others on their gardening journey.

We invite you to share your stories, ask questions, because if a thing has bothered you it will bother others too. Someone may have a solution ! No question is too small. There is learning for everyone involved, for you, for me (yes, I learn from every question), for us all. Exciting stuff !

We are starting on a new journey. Every week we will profile your letters ! The best stories and questions we receive.

SEARCH

Order the Kindle E-book for the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023

Recent Articles

-

garden for life is a blog about saving the earth one garden at a time

Apr 18, 25 01:18 PM

The garden for life blog has short articles on gardening for biodiversity with native plants and regenerating soil for climate amelioration and nutritious food -

Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, Cape Town's most endangered native vegetation!

Apr 18, 25 10:36 AM

Cape Flats Sand Fynbos, a vegetation type found in the super diverse Cape Fynbos region is threatened by Cape Town's urban development and invasive alien plants -

Geography Research Task

Jan 31, 25 11:37 PM

To whom it may concern My name is Tanyaradzwa Madziwa and I am a matric student at Springfield Convent School. As part of our geography syllabus for this

"How to start a profitable worm business on a shoestring budget

Order a printed copy from "Amazon" at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

or a digital version from the "Kindle" store at the SPECIAL PRICE of only

Prices valid till 30.09.2023